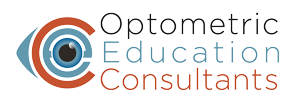

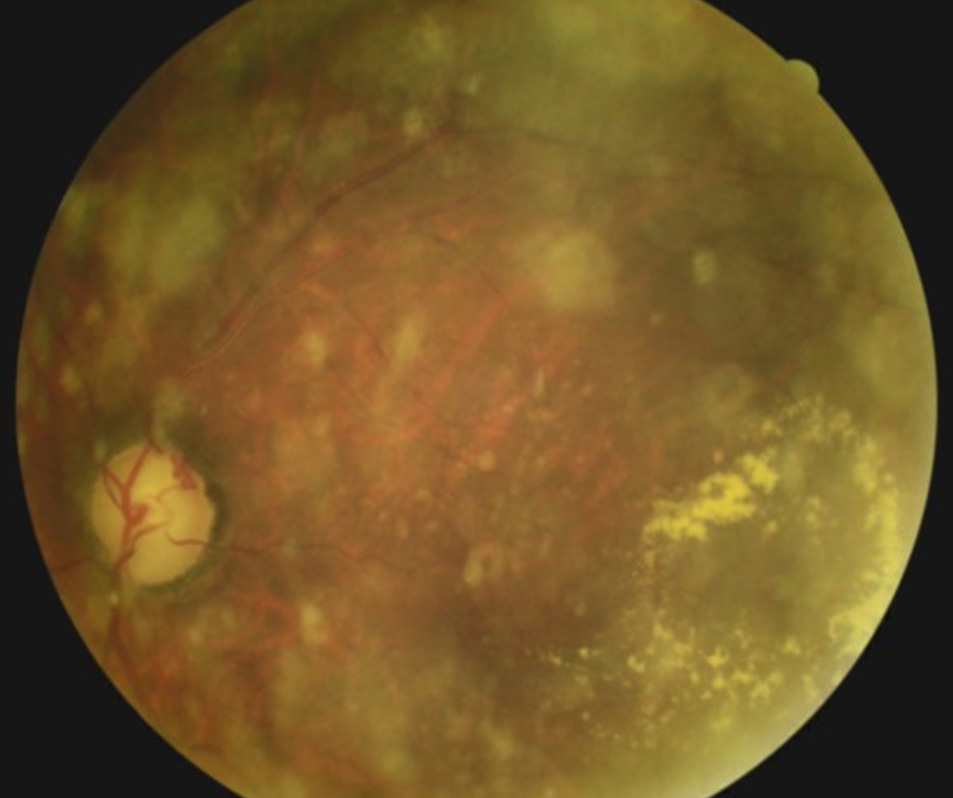

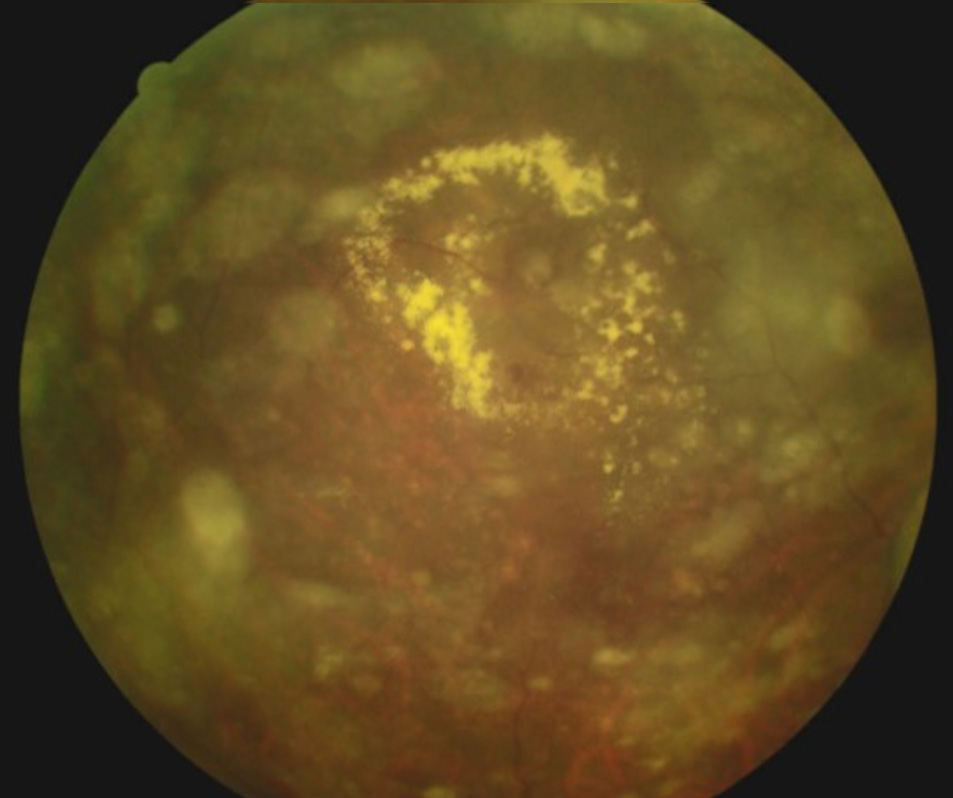

An 84-year-old African-American man with a history of glaucoma presented for consultation and care. Review of past records indicated that he had also been diagnosed the previous year with dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) OD and wet AMD OS with a circinate ring of exudates temporal to the left macula. He reported never following through with a retinal consultation for the AMD. On today’s visit, he reported a reduction of vision in his right eye for the past week. He was 20/50 in each eye. Dilated fundus examination revealed an extensive hemi-retinal vein occlusion in the right eye, advanced glaucomatous disc damage OU, scattered retinal drusen OU, asteroid hyalosis OS, disc collaterals OS and curiously a circinate ring of exudates OS nearly identical to the description from the previous record. Macular degeneration in a patient of African descent is a very uncommon occurrence.

The unchanging ring of exudates would not be consistent with wet AMD. Careful inspection revealed a saccular dilatation within the circinate exudates consistent with a retinal arterial microaneurysm (RAM). Retinal arterial macroaneurysms are acquired saccular or fusiform dilatations of the large arterioles of the retina. They are usually observed within the first three orders of bifurcation. Patients who develop RAM are typically in the 50-80 year-old age range. In many cases, un-ruptured lesions remain asymptomatic until discovered during routine dilated exams. Even without loss of function, by the time the patient presents, there has often been significant leakage into surrounding areas manifesting as visible exudates with variable presentations of pre-, intra-, and/or sub-retinal hemorrhage.

These balloon-like formations are caused by a break in the internal elastic lamina of the arteriole wall, through which serum, lipids and blood exude into the surrounding retina. The lesions seem to have an affinity for the bifurcations of vessels where structural integrity is weakest.

The natural course of RAM typically involves spontaneous sclerosis and thrombosis, particularly after hemorrhaging. For this reason, so long as there is no increased threat of macular hemorrhage, periodic observation is indicated. Asymptomatic non-leaking RAM may be monitored at 4-6 month intervals. If there is leakage in the form of exudation and/or hemorrhage that does not threaten the macula, then monitoring at 1-3 month intervals is indicated. If hemorrhage threatens or involves the macula or if there is persistent macular edema reducing vision or creating visual field loss, then direct photocoagulation of the RAM may speed resolution. The visual prognosis for eyes with ruptured or leaking RAM depends on the degree and type of macular involvement. In most cases, there is gradual and spontaneous involution concurrent with hemorrhage resorption. Intravitreal bevacizumab has shown promise as an effective therapy for complicated RAM and cases with submacular exudation.