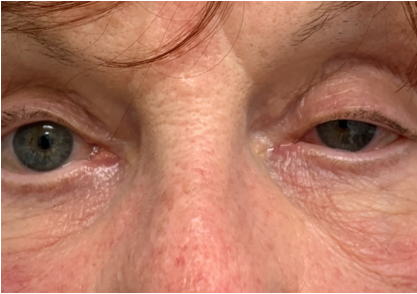

Left ptosis and miosis

Neck incision following parathyroid surgery

A 73-year-old woman presented urgently with a sudden left ptosis. She noticed it immediately after undergoing parathyroid surgery to remove 3 adenomas the day before. At first, she and her family thought it might have been due to the surgical anesthesia, but when it didn’t resolve the next day, the surgeon directed her to the emergency room out of fear of stroke. At the ER she had a CT scan of the brain which showed no abnormalities.

When she presented for ocular consultation, she had left ptosis and miosis with pupillary dilation lag in dim light. She also mentioned that she had a headache and an ache in her left eye as well. Instillation of 0.5% apraclonidine (Iopidine) elevated her eye lid and dilated her pupil, confirming that she had a left Horner’s Syndrome.

While neck surgery was superficially sufficient to explain her new onset Horner’s syndrome, it did not readily account for her headache and eye pain. Ocular inspection showed no abnormalities to account for her ocular discomfort. Possible carotid artery dissection was discussed, but the patient was resistant to any further intervention and would not go back to the ER as she had been there earlier in the day and maintained that her imaging was normal. Review of the neuroimaging report revealed that she had a CT of the brain to rule out hemorrhagic stroke, but the area of concern in the neck was not imaged. Due to the remote possibility that she may have a carotid artery dissection, she was prescribed 81 mg aspirin daily.

Phone follow-up the next day revealed that she felt much better with her headache and ocular discomfort dissipating. She stated that she had recovered from the physical and emotional exhaustion from the surgery and ER visit. She now agreed to further assessment of her Horner’s syndrome. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head and neck was ordered and scheduled. The results revealed that she did indeed have an acute left carotid artery dissection. Upon receiving the results, her aspirin was increased to a full 325 mg daily and she was seen by a stroke neurologist the next day. Her carotid dissection continues to heal and she therapeutically uses 0.5% Iopidine once daily in her left eye for cosmesis as it relieves her ptosis.

Horner’s syndrome is characterized by an interruption of the sympathetic nerve supply somewhere between its hypothalamic origin and the eye. Clinical findings can include ptosis, pupillary miosis, and, in some cases, facial anhidrosis. Apraclonidine is an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist which stimulates alpha-1 receptors to a negligible degree in a normal eye. A Horner’s syndrome pupil undergoes denervation hypersensitivity with upregulation of both the number and sensitivity of available receptors. When a very weak alpha-1 adrenergic agonist is applied, the hypersensitive pupil dilates while the normal pupil has no effect. Pupil dilation in suspected Horner’s syndrome is considered diagnostic. Additionally, ptosis also markedly improves with this medication.

In patients with new onset Horner’s syndrome concurrent with recent ipsilateral neck trauma, neck and face pain, ipsilateral transient monocular visual loss, or contralateral transient weakness or numbness, acute cervical carotid dissection must be immediately suspected. Carotid artery dissection is a linear tear in the vessel wall that allows for thrombus formation and possible subsequent embolization. In this case, there is a substantial risk of hemispheric stroke within the first two weeks of onset. Cervical carotid artery dissection is a relatively common cause of acute onset Horner’s syndrome. As the sympathetic fibers travel with the carotid artery within the neck, damage to the vessel can result in Horner’s syndrome. New onset Horner’s syndrome with head, neck, eye or face pain or after recent neck trauma must be emergently evaluated for carotid artery dissection. Patients will need stroke prophylaxis while the vessel wall heals and embolic risk dissipates.

Excellent. Thank you!