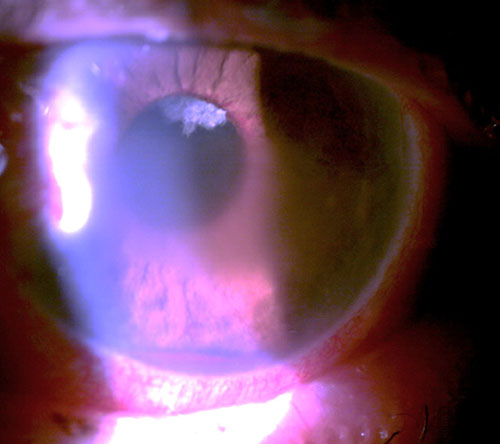

An 82 year old man presented complaining of a moderately painful left eye of approximately 2-week duration. He was both diabetic and hypertensive. He was 20/25 OD and bare light perception OS. His intraocular pressure (IOP) was 23 mm Hg OD and 62 mm Hg OS. His left eye manifested central microcystic corneal edema, florid iris neovascularization, and hyphema. Gonioscopically, his right angle was open to at least scleral spur while his left angle was closed with peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) for 1800 with hyphema and angle neovascularization for the remaining part of the angle. The corneal edema, circulating hyphema, and poor dilation prevent fundus examination.

Clearly this was an acutely urgent case of neovascular glaucoma (NVG). Patients with NVG typically present with a chronically red, painful eye, which often has significant vision loss. There frequently is an antecedent history of a retinal vessel occlusion, carotid artery disease, chronic retinal detachment, or advanced diabetic retinopathy. There will be visible neovascularization of the iris (NVI) and angle (NVA). The patient will typically have significant corneal edema, anterior segment inflammation, anterior chamber cell and flare reaction, and elevated intraocular pressure due to synechial angle closure, often exceeding 60 mm Hg.

Retinal hypoxia induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to act upon healthy endothelial cells of viable capillaries to stimulate the formation of a fragile new plexus of vessels (neovascularization). VEGF diffuses forward to the nearest area of viable capillaries, namely the posterior iris. Neovascularization buds off of the capillaries of the posterior iris, grows along the posterior iris, through the pupil, along the anterior surface of the iris, and then into the angle. Once in the angle, the neovascularization, along with attendant fibrovascular support membrane will block the trabecular meshwork with progressive PAS.

Neovascular glaucoma requires prompt and aggressive therapy. This involves control of the intraocular pressure and inflammation as well as management of the retinal ischemia as well as any precipitating conditions. Upon first presentation, a strong cycloplegic such as atropine 1% BID as well as a topical steroid such as prednisolone acetate 1% or difluprednate 0.05% QID should be prescribed. The fact that the angle may be closed with PAS does not preclude pharmacologic mydriasis from atropine. Neither does the elevated IOP disqualify steroid use. This will greatly add to patient comfort. Aqueous suppressants in the form of beta blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and alpha adrenergic agonists may be used in order to temporarily reduce IOP. Definitive treatment is best accomplished with pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) to destroy ischemic retina, minimize oxygen demand of the eye, and reduce the amount of VEGF being released. While PRP is the most definitive treatment for the neovascularization causing NVG, the advent and use of antiangiogenic drugs has proven to be a valuable adjunct.

The patient presenting here was prescribed atropine 1% BID, prednisolone acetate 1% QID, and brinzolamide/brimonidine fixed combination TID in the left eye. Upon meeting with the retinal specialist approximately 2 weeks later, his eye pain had disappeared, his IOP was now lowered to 24 mm Hg OS, and his cornea had clear enough to allow fundus examination. There was still iris neovascularization, but the hyphema had cleared. Fundus examination of the left eye revealed combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion. He received an intravitreal injection of an anti-VEGF agent and was scheduled for PRP.