A 13 year old female was referred for painless reduced vision (20/40) in her left eye with a concurrent abnormal screening visual field, reportedly elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and an afferent pupillary defect. Her previous exam was 3 weeks earlier and she had been previously referred to an ophthalmologist over a year earlier by another optometrist, but her mother did not know why and did not take her. When presented with painless vision loss in a young patient with these findings, there are numerous diagnostic possibilities.

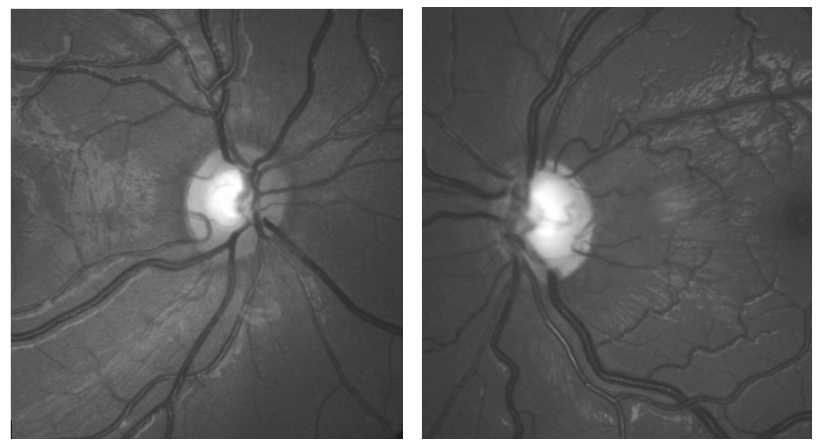

The key piece of diagnostic information was her IOP: she measured 28 mm Hg OD and 43 mm Hg OS by Goldmann applanation. Her pachymetry was slightly thick at 593µ OD and 595µ OS, but these values will not significantly impact an IOP of 43 mm Hg. There were no biomicroscopic or gonioscopic abnormalities and both angles were open. The reason for the pronounced visual field loss, reduced vision, and left afferent pupillary defect was asymmetric glaucomatous damage. She was diagnosed with juvenile open angle glaucoma (JOAG).

Glaucoma can afflict infants and children in several ways. Conditions such as inflammation or trauma can contribute to elevated intraocular pressure in secondary glaucoma, while congenital abnormalities of the trabecular meshwork development can result in infantile glaucoma. Lesser known, however, is juvenile open angle glaucoma, which afflicts children and young adults similar to primary open angle glaucoma, with no identifiable trabecular meshwork abnormalities or other secondary causes. Intraocular pressure elevation develops between ages 3 and 16 years. Typically the IOP level is quite high; there are no “normotensive” JOAG cases. The disease tends to be more aggressive and progressive than adult POAG.

Treating children and young adults with JOAG presents challenges and medical therapy isn’t the same as with older adults. Pediatric use is considered to be off label, though it is commonly done. Topical beta blockers are a safe and effective class when used in children. Prostaglandin analogs (PGA) are safe and well tolerated, but unfortunately not very effective in the pediatric glaucoma population. Children where PGA efficacy is best demonstrated are older, typically commensurate with puberty. When used in children, topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) are a safe and effective means by which to lower IOP. Brimonidine, though effective in lowering IOP in children, crosses the blood-brain barrier and can potentially affect the central nervous system (CNS). This medication has demonstrated an unacceptable level of adverse events in children (even inducing coma) and should not be used if possible, and definitely not before the age of 8 years.

In the young girl presented here, prostaglandin analogs predictably had no effect. She eventually ended up using dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination (Cosopt), which lowered her IOP to a range of 15-17 mm in each eye.

Another great case. Despite a very impressive initial IOP drop with the fixed combination, this young woman will likely need additional treatment in the future … would a PGA tend to work a bit better when she is older, or if it’s ineffective at age 13, will it always be ineffective? Thx.

No, I expect a PGA should work when she’s a bit older. There really is no explanation for this phenomenon.

Thanks for the comments